CJMonsoon: Global Monsoon Patterns and Climate Impact Now

The term “cjmonsoon” represents a fascinating intersection of meteorological phenomena that shape the lives of billions of people across the globe. Monsoons are not merely seasonal rain patterns but complex atmospheric systems that influence agriculture, economy, culture, and the very fabric of societies in affected regions. This comprehensive article delves into the multifaceted nature of monsoon systems, examining their formation, characteristics, regional variations, and the profound impact they have on human civilization and natural ecosystems.

Understanding the Fundamental Nature of Monsoon Systems

Monsoons represent one of the most dramatic and predictable climate phenomena on Earth, characterized by seasonal reversals in wind direction and associated changes in precipitation patterns. The word “monsoon” derives from the Arabic word “mausim,” meaning season, which perfectly encapsulates the cyclical nature of these atmospheric events. Unlike typical weather patterns that can be irregular and unpredictable, monsoons follow a relatively consistent annual cycle, making them both a blessing and a challenge for the regions they affect.

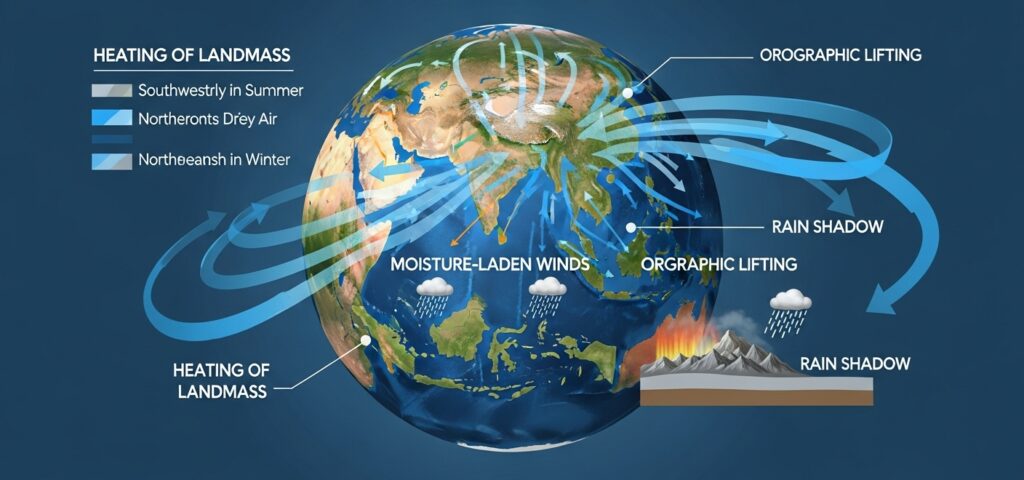

The fundamental mechanism driving monsoon systems involves differential heating between land and ocean surfaces. During summer months, landmasses heat up more rapidly than adjacent ocean waters, creating a thermal low-pressure zone over the continent. This pressure differential draws moisture-laden air from the ocean toward the land, resulting in the characteristic heavy rainfall associated with monsoons. Conversely, during winter months, the land cools faster than the ocean, reversing the pressure gradient and wind direction, typically bringing dry conditions to the same regions that experienced abundant rainfall just months earlier.

The scientific understanding of monsoons has evolved significantly over the past century. Early meteorologists recognized the seasonal wind shifts but lacked the tools to comprehend the full complexity of these systems. Modern satellite technology, advanced computer modeling, and coordinated international research efforts have revealed that monsoons are influenced by a complex interplay of factors including ocean temperatures, atmospheric circulation patterns, topography, and even vegetation cover. The El Niño Southern Oscillation, Indian Ocean Dipole, and other large-scale climate phenomena can significantly modify monsoon behavior, adding layers of complexity to prediction and analysis.

The Asian Monsoon: Earth’s Most Influential Weather System

The Asian monsoon system stands as the most extensive and influential monsoon circulation on the planet, directly affecting the lives of approximately four billion people across South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia. This massive atmospheric system is actually composed of several interconnected subsystems, including the Indian monsoon, the East Asian monsoon, and the Southeast Asian monsoon, each with distinct characteristics but sharing common driving mechanisms.

The Indian monsoon, often simply called “the monsoon” due to its profound significance, typically arrives in Kerala on the southwestern coast of India around June 1st, though this date can vary by several weeks depending on prevailing atmospheric conditions. From this initial landfall, the monsoon progresses northward across the subcontinent over the following six to eight weeks, bringing life-giving rains to a region that depends heavily on this seasonal precipitation for agriculture, water resources, and economic stability. The monsoon’s arrival is not a gradual transition but often a dramatic event marked by sudden, heavy downpours that transform the landscape from parched brown to vibrant green within days.

The topography of the Asian continent plays a crucial role in shaping monsoon behavior. The Himalayan mountain range, the highest on Earth, acts as a massive barrier that channels monsoon winds and forces air masses to rise, cool, and release their moisture. This orographic effect creates some of the wettest places on the planet, with locations like Mawsynram and Cherrapunji in northeastern India receiving over 11,000 millimeters of rainfall annually, almost entirely during the monsoon season. The Tibetan Plateau, elevated high above sea level, also influences monsoon dynamics by acting as an elevated heat source that enhances the thermal contrast between land and ocean.

Regional Variations and Characteristics of Global Monsoon Systems

While the Asian monsoon receives the most attention due to its impact on human populations, monsoon systems exist on every continent except Antarctica. The African monsoon, particularly the West African monsoon, plays a critical role in the climate and livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people across the Sahel region and beyond. This system brings the Intertropical Convergence Zone northward during summer, delivering rainfall to regions that would otherwise be extremely arid. The timing and intensity of the West African monsoon have profound implications for food security, as the region’s agricultural systems are almost entirely dependent on these seasonal rains.

The North American monsoon, though less intense than its Asian and African counterparts, significantly influences weather patterns across the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. This monsoon typically develops in July and August, bringing afternoon thunderstorms to normally arid regions like Arizona, New Mexico, and the Mexican states of Sonora and Sinaloa. While the total precipitation is modest compared to other monsoon systems, it represents a crucial water source for these desert and semi-desert environments, supporting unique ecosystems and providing relief from extreme summer heat.

Australia experiences a robust monsoon system in its northern regions, with the Australian monsoon typically active from December through March, coinciding with the Southern Hemisphere summer. Darwin, the capital of the Northern Territory, receives approximately 90 percent of its annual rainfall during the monsoon season, experiencing dramatic thunderstorms and heavy downpours that contrast sharply with the dry season’s clear skies and minimal precipitation. The Australian monsoon is closely linked to the broader Indo-Pacific warm pool and can be influenced by climate phenomena such as the Madden-Julian Oscillation.

South America’s monsoon system, centered over the Amazon basin and extending into southeastern Brazil, represents another significant monsoon circulation. This system drives the wet season across much of tropical and subtropical South America, with profound implications for the world’s largest rainforest ecosystem. The South American monsoon exhibits complex interactions with the Amazon rainforest itself, as the forest’s transpiration contributes moisture to the atmosphere, effectively reinforcing and sustaining the monsoon circulation in a fascinating example of biosphere-atmosphere coupling.

Comparative Analysis of Monsoon Systems Across Different Regions

Understanding the similarities and differences among monsoon systems globally provides valuable insights into the fundamental atmospheric dynamics driving these phenomena and the specific regional factors that create variation. While all monsoon systems share basic characteristics—seasonal wind reversals, concentrated seasonal rainfall, and thermal contrasts between land and ocean—they differ significantly in timing, intensity, spatial extent, and societal impacts. Comparative analysis helps identify universal principles while recognizing the unique character of each regional monsoon.

The following table presents key characteristics of major global monsoon systems, highlighting their diversity and common features:

| Monsoon System | Primary Season | Average Rainfall (mm) | Population Affected (millions) | Key Economic Sectors | Primary Climate Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Asian | June-September | 750-2500 | 1800 | Agriculture, Hydropower | Indian Ocean temperatures, Himalayan topography |

| East Asian | June-September | 600-1600 | 1500 | Agriculture, Manufacturing | Pacific Ocean conditions, Tibetan Plateau |

| Southeast Asian | May-October | 1500-3000 | 650 | Agriculture, Forestry | Maritime continent warmth, ENSO influence |

| West African | June-September | 400-1200 | 500 | Agriculture, Livestock | Atlantic temperatures, Sahel vegetation |

| North American | July-September | 150-400 | 25 | Agriculture, Tourism | Gulf of California heating, Mexican topography |

| South American | October-March | 1200-2500 | 280 | Agriculture, Hydropower | Amazon forest-atmosphere interaction |

| Australian | December-March | 1200-1800 | 3 | Mining, Tourism, Agriculture | Indo-Pacific warm pool, MJO activity |

This comparative framework reveals several important patterns. Tropical monsoon systems generally deliver higher rainfall totals than subtropical systems, reflecting greater atmospheric moisture availability in warmer regions. Systems affecting Asia support by far the largest populations and have the most profound economic significance globally. Topography plays crucial roles in multiple systems, with mountain ranges and elevated plateaus influencing wind patterns and precipitation distribution. Large-scale ocean-atmosphere phenomena like ENSO, the Indian Ocean Dipole, and the Madden-Julian Oscillation affect multiple monsoon systems, creating potential for climate teleconnections where variations in one region relate to variations elsewhere.

The Agricultural Imperative: Monsoons and Food Security

Agriculture’s intimate relationship with monsoon systems cannot be overstated, particularly in regions where irrigation infrastructure is limited or absent. In India alone, approximately 60 percent of the cultivated area remains dependent on rainfall, making the monsoon the primary determinant of agricultural productivity and rural livelihoods. Rice, wheat, cotton, sugarcane, and countless other crops follow planting and harvesting schedules precisely calibrated to monsoon onset, progression, and withdrawal. A delayed monsoon can force farmers to postpone planting, reducing growing seasons and yields, while an early withdrawal can damage crops before they reach maturity.

The economic implications of monsoon variability extend far beyond individual farms. Agricultural production influenced by monsoon performance affects food prices, inflation rates, rural employment, urban migration patterns, and overall economic growth in monsoon-dependent nations. India’s Ministry of Finance closely monitors monsoon progress and forecasts, as agricultural performance driven by monsoon rainfall can influence the nation’s GDP growth rate by one to two percentage points. Similar relationships exist in other monsoon-affected countries, where the seasonal rains represent a critical economic variable that policymakers and business leaders watch with intense interest.

Traditional agricultural knowledge systems have developed sophisticated responses to monsoon variability over millennia. Farmers in monsoon regions have cultivated diverse crop portfolios, developed drought-resistant varieties, practiced intercropping to hedge against variable rainfall, and maintained complex indigenous forecasting techniques based on natural indicators. Modern agricultural science has built upon these traditional foundations, developing improved crop varieties, precision irrigation systems, and weather-indexed insurance products designed to help farmers manage monsoon-related risks. The integration of traditional knowledge with contemporary technology represents a promising approach to enhancing agricultural resilience in the face of climate variability and change.

Water Resources Management in Monsoon-Influenced Regions

The seasonal concentration of rainfall characteristic of monsoon climates presents profound challenges for water resources management. Regions that receive 80 to 90 percent of their annual precipitation during a three to four month monsoon period must capture, store, and manage this water to meet year-round needs for drinking, agriculture, industry, and ecosystem maintenance. This imperative has driven the construction of massive water infrastructure projects, including some of the world’s largest dams, reservoir systems, and inter-basin water transfer schemes.

India’s water storage infrastructure, built largely in the decades following independence, reflects the nation’s efforts to harness monsoon rainfall and buffer against seasonal and interannual variability. Major dam projects like the Bhakra Nangal, Hirakud, and Sardar Sarovar have created enormous reservoirs that store monsoon runoff for use during the dry season. These projects have enabled year-round irrigation, hydroelectric power generation, and more reliable municipal water supplies, contributing significantly to economic development. However, they have also generated controversy regarding displacement of communities, environmental impacts, downstream effects, and questions about whether such large-scale infrastructure represents the most sustainable approach to water management.

Traditional water harvesting systems offer complementary approaches to managing monsoon rainfall that deserve renewed attention and investment. Stepwells in western India, tank systems in the south, johads in Rajasthan, and countless other indigenous water storage and recharge structures were designed specifically to capture and store monsoon runoff at local and community scales. Many of these systems fell into disrepair during the twentieth century as governments and development agencies favored large-scale infrastructure, but recent decades have seen growing recognition of their value. Community-led efforts to restore traditional water harvesting systems have demonstrated impressive results, raising groundwater levels, increasing agricultural productivity, and enhancing local resilience to drought and climate variability.

Monsoon Forecasting: Science, Technology, and Societal Needs

The ability to forecast monsoon behavior—its onset, progression, intensity, and spatial distribution—represents one of the most important applications of meteorological science in monsoon-affected regions. Accurate forecasts enable farmers to make informed planting decisions, allow water resource managers to optimize reservoir operations, help energy planners anticipate hydroelectric power availability, and permit disaster management agencies to prepare for potential flooding. The societal demand for reliable monsoon forecasts has driven sustained investment in meteorological infrastructure, research, and forecasting capabilities.

Seasonal monsoon forecasting attempts to predict overall rainfall totals and patterns weeks to months in advance, providing strategic information for agricultural planning and resource allocation. These forecasts rely on statistical relationships between monsoon rainfall and predictor variables such as sea surface temperatures, atmospheric pressure patterns, snow cover, and other climate indicators. India Meteorological Department issues its first long-range monsoon forecast in April, providing an initial assessment of expected seasonal rainfall, followed by updates in June and July as the monsoon season unfolds. While these forecasts have improved significantly over recent decades, inherent limitations in predictability mean that seasonal forecasts remain probabilistic rather than deterministic, expressing likelihoods rather than certainties.

Short-term forecasting operating on timescales of hours to days has benefited enormously from advances in numerical weather prediction, satellite observations, and computing power. Modern forecast models can now predict the timing and intensity of individual monsoon weather systems with reasonable accuracy several days in advance, enabling more precise warnings for heavy rainfall events, potential flooding, and other hazardous conditions. The proliferation of mobile phones and internet connectivity has revolutionized forecast dissemination, allowing meteorological agencies to reach millions of users directly with location-specific forecasts and warnings. This improved information flow has tangible benefits for public safety, agricultural decision-making, and daily planning.

Climate Change and the Future of Monsoon Systems

The relationship between anthropogenic climate change and monsoon systems represents one of the most pressing questions in contemporary climate science, with profound implications for billions of people dependent on monsoon rainfall. Climate models project complex and sometimes regionally varied changes to monsoon systems as greenhouse gas concentrations continue to rise and global temperatures increase. Understanding these potential changes and their uncertainties is essential for adaptation planning and climate policy in monsoon-affected regions.

Most climate models project an intensification of monsoon rainfall, with increased total precipitation over monsoon seasons despite potential reductions in the number of rainy days. This projection reflects the basic physics of a warmer atmosphere, which can hold more moisture and potentially release it in more intense rainfall events. However, the models also suggest potential changes to monsoon timing, with some projections indicating later onset dates or earlier withdrawal, effectively shortening the monsoon season even as total rainfall increases. Such changes could have significant agricultural implications, particularly for rain-fed farming systems calibrated to current monsoon patterns.

Observational evidence of monsoon changes over recent decades presents a complex picture. Long-term rainfall records from India show a weakening trend in monsoon circulation and some evidence of declining seasonal totals during the latter half of the twentieth century, though these trends have not continued uniformly into the twenty-first century. Meanwhile, the frequency of extreme rainfall events—very heavy downpours that can cause flooding—appears to be increasing, consistent with theoretical expectations for a warming climate. The spatial distribution of monsoon rainfall also shows changing patterns, with some regions receiving increased precipitation while others experience declining trends.

Monsoons and Natural Ecosystems: Biodiversity Hotspots and Ecological Processes

Monsoon climates support some of Earth’s most diverse and productive ecosystems, from tropical rainforests to seasonal deciduous forests, wetlands, grasslands, and coastal mangrove systems. The seasonal rhythm of monsoon rainfall drives ecological processes, shapes species distributions, and creates unique adaptations that allow plants and animals to thrive in environments characterized by extreme seasonal contrasts between wet and dry conditions. Understanding these ecological relationships is essential for conservation planning and ecosystem management in monsoon regions.

Tropical monsoon forests, found across South and Southeast Asia, parts of Africa, and northern Australia, exhibit remarkable biodiversity despite experiencing a distinct dry season. These forests have developed strategies to cope with seasonal water stress, including deciduous species that shed leaves during the dry season and evergreen species with drought-resistant adaptations. The timing of flowering, fruiting, and leaf flush in monsoon forests is often precisely synchronized with monsoon onset, allowing plants to take maximum advantage of the favorable growing conditions. This phenological precision creates temporal patterns in resource availability that structure animal communities and shape migration patterns, breeding cycles, and feeding strategies.

Wetland ecosystems in monsoon regions undergo dramatic seasonal transformations, expanding enormously during the monsoon season and contracting during the dry season. The Pantanal in South America, the Okavango Delta in southern Africa, and countless smaller wetland systems follow this pattern, supporting extraordinary biodiversity and providing critical ecosystem services. These wetlands serve as breeding grounds for fish, birds, and other wildlife, filter and purify water, recharge groundwater, and buffer against floods. The seasonal pulse of monsoon rainfall drives productivity in these systems, creating boom-and-bust cycles that many species have evolved to exploit.

Cultural and Religious Significance of Monsoons Across Civilizations

Monsoons have profoundly shaped human cultures, particularly in regions where seasonal rainfall patterns dominate the annual rhythm of life. Agricultural societies that emerged in monsoon regions developed calendars, festivals, religious practices, and cultural traditions intimately connected to the monsoon cycle. These cultural connections reflect not only the practical importance of monsoons for survival and prosperity but also deeper relationships between human communities and the natural rhythms that structure their existence.

In Hindu tradition, the arrival of the monsoon is celebrated through numerous festivals and religious observances that acknowledge the life-giving nature of seasonal rains. The festival of Teej, celebrated primarily in northern India and Nepal, welcomes the monsoon with songs, dances, and rituals honoring the goddess Parvati. The god Indra, associated with rain and thunderstorms in Vedic literature, occupies a central place in the Hindu pantheon, reflecting the civilizational importance of monsoon rainfall. Classical Indian literature, from ancient Sanskrit texts to medieval poetry, is replete with elaborate descriptions of the monsoon season, its dramatic onset, the transformation of the landscape, and the emotions it evokes.

Agricultural communities across monsoon regions have developed intricate bodies of traditional ecological knowledge related to monsoon forecasting and agricultural timing. Farmers observed natural indicators—the flowering of certain trees, the behavior of animals, the appearance of particular insect species, cloud formations, wind patterns—to predict monsoon onset and intensity. While modern meteorological forecasting has partially displaced these traditional methods, they represent sophisticated systems of environmental observation and interpretation developed over countless generations. Contemporary research increasingly recognizes the value of traditional forecasting knowledge, particularly at local scales where it can complement scientific forecasts.

Urban Challenges: Monsoons and City Planning in the Twenty-First Century

Rapid urbanization in monsoon-affected regions has created new challenges for managing seasonal rainfall in city environments. Many of Asia’s fastest-growing cities—Mumbai, Bangkok, Jakarta, Manila, Dhaka—are located in monsoon zones and experience intense rainfall that strains urban infrastructure and creates significant flooding problems. The combination of heavy monsoon downpours, aging drainage systems, unplanned development, and loss of natural water absorption surfaces creates conditions ripe for urban flooding that disrupts transportation, damages property, and sometimes claims lives.

Mumbai, India’s financial capital, exemplifies the challenges that monsoon cities face. The city receives approximately 90 percent of its annual rainfall during the monsoon months of June through September, with extreme events sometimes delivering more than 200 millimeters in a single day. The city’s drainage system, much of it dating to the colonial era, struggles to handle such intense rainfall, particularly when high tides prevent outflow to the sea. Informal settlements built on flood-prone land and along drainage channels exacerbate flooding problems while placing vulnerable populations at greatest risk. Similar challenges exist in cities across monsoon Asia, from Chennai to Colombo to Ho Chi Minh City.

Urban planning and infrastructure development in monsoon cities increasingly incorporates climate resilience principles and nature-based solutions. Restoration of urban wetlands, creation of permeable surfaces, construction of retention ponds and detention basins, and implementation of green infrastructure can enhance cities’ capacity to absorb and manage intense monsoon rainfall. Singapore’s Active, Beautiful, Clean Waters program demonstrates how urban water management can be reimagined, transforming concrete drainage channels into naturalized streams and wetlands that provide flood management while enhancing urban livability and biodiversity. Such approaches require substantial investment and political will but offer more sustainable alternatives to endless expansion of conventional gray infrastructure.

Economic Dimensions: Monsoons as Drivers of Regional and Global Economics

The economic significance of monsoon systems extends far beyond agriculture to encompass energy production, industrial water supplies, transportation, construction, retail sectors, and financial markets. In India, the monsoon’s influence on agricultural production creates ripple effects throughout the economy, affecting food prices, rural purchasing power, demand for manufactured goods, and ultimately overall economic growth. Good monsoon years typically boost GDP growth, reduce inflation, and improve fiscal balances, while poor monsoon years have opposite effects, demonstrating the enduring importance of rainfall despite industrialization and economic diversification.

Energy systems in monsoon regions exhibit strong seasonal patterns driven by rainfall availability. Hydroelectric power generation peaks during and immediately after monsoon seasons when reservoir levels are high, providing clean, renewable energy that can reduce reliance on fossil fuels. Countries like Nepal, Bhutan, and regions of India derive substantial portions of their electricity from hydropower, making energy security closely linked to monsoon performance. Conversely, poor monsoon years that reduce reservoir levels can create energy shortages, forcing increased use of expensive and polluting thermal power plants. The challenge of managing energy systems in monsoon climates highlights the importance of diverse energy portfolios that can buffer against hydrological variability.

Financial markets increasingly recognize monsoon risk as a significant factor affecting company performance and investment returns. Insurance companies offer weather-indexed agricultural insurance products that pay out based on rainfall measurements rather than crop damage assessments, reducing moral hazard and transaction costs. Commodity traders monitor monsoon forecasts closely, as rainfall patterns influence production and prices for agricultural products from rice to coffee to cotton. Weather derivatives allow companies to hedge against monsoon-related risks, though these instruments remain underdeveloped in many regions where they could provide substantial value. The financialization of monsoon risk represents both opportunity and peril, potentially providing useful risk management tools while also creating new vulnerabilities if not properly regulated.

Disaster Risk and Monsoon-Related Hazards

While monsoons bring essential rainfall, they also generate significant natural hazards including floods, landslides, cyclones, and lightning that claim thousands of lives annually and cause billions of dollars in economic damages. The concentration of precipitation during monsoon seasons means that river systems must accommodate enormous volumes of water within short timeframes, frequently exceeding channel capacities and causing extensive flooding. Low-lying areas, floodplains, and coastal zones are particularly vulnerable, often hosting dense populations with limited resources to cope with flood impacts.

Flooding represents the most widespread and recurrent monsoon-related hazard, affecting millions of people across South Asia, Southeast Asia, and other monsoon regions annually. Major flood events can displace entire communities, destroy crops and infrastructure, contaminate water supplies, and create public health emergencies. The 2010 Pakistan floods affected approximately 20 million people and inundated roughly one-fifth of the country’s total land area, demonstrating the catastrophic potential of extreme monsoon rainfall. Similar mega-floods have occurred throughout the monsoon zone, from Bangladesh to Thailand to northeastern India, highlighting the persistent vulnerability of populations living in flood-prone areas.

Landslides triggered by intense monsoon rainfall pose particular dangers in mountainous and hilly regions where steep slopes, weak geology, deforestation, and human settlement combine to create hazardous conditions. The Himalayan region, Western Ghats, and other mountain areas experience numerous landslides during each monsoon season, blocking roads, damaging infrastructure, and sometimes burying entire villages. Climate change projections suggesting increased rainfall intensity raise concerns about potentially greater landslide risk in the future, particularly in areas where land use changes have already destabilized slopes. Effective disaster risk reduction requires integrated approaches combining improved forecasting and early warning, land use planning that restricts development in high-risk areas, slope stabilization measures, and community preparedness programs.

Traditional Knowledge Systems and Indigenous Monsoon Wisdom

Long before modern meteorology developed, communities living in monsoon regions accumulated sophisticated knowledge about seasonal rainfall patterns, forecasting methods, water management strategies, and agricultural adaptations. This traditional ecological knowledge, passed through generations via oral traditions, practical demonstrations, and cultural practices, represents invaluable wisdom about living successfully in monsoon climates. Contemporary development approaches increasingly recognize the importance of respecting and incorporating traditional knowledge alongside scientific approaches.

Traditional monsoon forecasting systems employed detailed observations of natural phenomena to predict rainfall characteristics. Farmers noted the flowering times of particular tree species, the arrival and behavior of migratory birds, the appearance of certain insects, the formation and movement of clouds, wind patterns, and astronomical observations to develop forecasts. While these methods lacked the precision and lead time of modern forecasting, they provided locally relevant information and reflected deep understanding of local environmental conditions and their relationships to larger weather patterns. Research has found that traditional forecasts can achieve accuracy rates comparable to long-range statistical forecasts, particularly for local-scale predictions.

Water management traditions developed over centuries reflect adaptive responses to monsoon rainfall patterns and the challenge of water storage in tropical climates. The qanat systems of Iran and Afghanistan, baolis and johads of India, and various indigenous irrigation systems across monsoon regions demonstrate sophisticated engineering and social organization. These systems were typically managed communally, with elaborate rules governing water allocation, maintenance responsibilities, and conflict resolution. The decline of many traditional water management systems during the twentieth century has prompted efforts to revive and modernize them, combining traditional designs with contemporary materials and management approaches to create sustainable water solutions appropriate for local conditions.

Technological Innovations in Monsoon Monitoring and Management

Advances in technology have revolutionized humanity’s ability to monitor, forecast, and respond to monsoon systems. Satellite observations provide comprehensive views of atmospheric moisture, rainfall, cloud development, and circulation patterns impossible to obtain from ground-based networks alone. Weather radar networks detect and track individual storms, providing crucial information for short-term forecasts and warnings. Automated weather stations, including those deployed in remote and challenging environments, generate dense observational networks that feed into forecast models and climate monitoring systems.

The proliferation of mobile technology and internet connectivity has transformed how monsoon information reaches end users. Farmers can receive personalized, location-specific rainfall forecasts directly on their mobile phones, enabling more informed agricultural decisions. Weather apps provide real-time rainfall information, hourly forecasts, and severe weather alerts to hundreds of millions of users. Social media platforms have become important channels for disseminating weather information and warnings, though they also present challenges related to misinformation and unverified reports. The democratization of weather information represents a profound shift from earlier eras when such information was available only to government agencies and elite institutions.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques are increasingly applied to monsoon forecasting and analysis, offering potential to improve prediction skill by identifying complex patterns in large datasets. Neural networks trained on decades of atmospheric observations can sometimes outperform traditional statistical methods in seasonal forecasting. Machine learning algorithms help identify relationships between monsoon rainfall and climate indices, vegetation conditions, soil moisture, and other variables. These computational approaches complement rather than replace physical understanding, ideally combining data-driven insights with knowledge of atmospheric dynamics to achieve superior forecasts.

The following table illustrates the evolution of monsoon forecasting capabilities over time:

| Era | Forecasting Method | Lead Time | Key Limitations | Technological Basis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1900 | Traditional ecological indicators | Days to weeks | Qualitative, local scale only | Direct observation of natural phenomena |

| 1900-1960 | Statistical relationships, analog years | Seasonal average | No spatial detail, modest skill | Surface weather observations, statistical analysis |

| 1960-1990 | Numerical models, synoptic patterns | Seasonal to weekly | Coarse resolution, limited computing | Satellites, early numerical modeling, mainframe computers |

| 1990-2010 | Coupled ocean-atmosphere models | Seasonal to daily | Ensemble spread, systematic biases | Improved satellites, supercomputers, data assimilation |

| 2010-Present | High-resolution ensemble prediction | Sub-seasonal to nowcasting | Chaotic limits, initial condition uncertainty | AI/ML integration, advanced computing, dense observational networks |

This technological evolution has delivered measurable improvements in forecast skill and societal value. Modern seasonal forecasts explain significantly more variance in monsoon rainfall than forecasts available just two decades ago. Short-term forecasts now routinely provide accurate predictions three to five days in advance, compared to one to two days in earlier eras. These improvements translate directly into societal benefits through better agricultural planning, more effective disaster preparedness, optimized water resource management, and countless individual decisions informed by reliable weather information.

Future Perspectives: Adaptation and Resilience in a Changing Climate

Looking forward, monsoon-dependent regions face the twin challenges of managing inherent climate variability while adapting to long-term climate change. Building resilience requires integrated approaches that address multiple dimensions of vulnerability including infrastructure, institutions, information systems, livelihoods, and ecosystems. No single intervention suffices; rather, successful adaptation will emerge from portfolios of actions implemented across scales from individual households to national governments to international cooperation frameworks.

Infrastructure investments remain essential for managing monsoon rainfall and reducing vulnerability to floods and droughts. However, twenty-first century infrastructure should differ from twentieth century approaches, incorporating climate resilience from the design stage, embracing nature-based solutions alongside conventional engineering, planning for changing rather than stationary climate conditions, and prioritizing flexibility and adaptability. Green infrastructure that works with natural hydrological processes rather than against them offers particular promise, providing flood management, water quality improvement, groundwater recharge, and co-benefits for biodiversity and human wellbeing. The challenge lies in financing such approaches and overcoming institutional preferences for conventional solutions.

Agricultural adaptation to changing monsoon patterns requires diversified strategies supporting both autonomous adaptation by farmers and planned adaptation by government agencies and development organizations. Crop breeding programs developing varieties tolerant to heat, drought, waterlogging, and salinity can provide crucial tools for farmers facing increased climate variability. Improved weather information services, agricultural extension, and climate-informed advisories enable farmers to make better-informed decisions about crop selection, planting timing, and management practices. Social protection programs including crop insurance, cash transfers, and employment guarantees can help households manage climate-related shocks without falling into poverty traps.

Conclusion: Embracing the Complexity of Monsoon Systems

Monsoons represent far more than seasonal rainfall patterns; they are complex earth system phenomena that connect atmosphere, ocean, land surface, and biosphere in intricate ways that science is still working to fully understand. These systems have shaped human civilizations for millennia, supporting some of the world’s most productive agricultural regions and densest populations while also creating significant hazards and vulnerabilities. The relationship between human societies and monsoon systems continues to evolve as populations grow, climate changes, technology advances, and understanding deepens.

The challenges facing monsoon regions in the coming decades are substantial. Climate change introduces new uncertainties even as growing populations increase demands on monsoon-dependent water resources and agricultural systems. Urbanization creates novel vulnerabilities in cities ill-equipped to handle intense rainfall. Environmental degradation including deforestation, soil erosion, and wetland loss undermines natural systems that help regulate hydrological cycles. These challenges require urgent attention and coordinated responses drawing on the best available science, technology, traditional knowledge, and human ingenuity.

Yet there are also reasons for optimism. Scientific understanding of monsoon systems has advanced dramatically, enabling better forecasts and earlier warnings. Technology provides unprecedented capabilities for monitoring, analyzing, and disseminating information about monsoon conditions. International cooperation on climate research and disaster risk reduction has strengthened. Communities and governments are implementing innovative adaptation strategies that build resilience while supporting sustainable development. Success stories exist across monsoon regions, demonstrating that informed action can reduce vulnerability and harness the benefits of seasonal rainfall while managing its risks.

The future of monsoon regions will be determined by choices made today about infrastructure, institutions, land use, emissions, and development pathways. By recognizing the profound importance of monsoon systems, respecting their complexity, embracing both scientific and traditional knowledge, investing in resilience, and acting with foresight, societies can navigate the challenges ahead while preserving and enhancing the life-giving benefits that monsoons provide. The monsoon is not merely a weather phenomenon to be endured but a defining feature of regional identity and a source of renewal that has sustained civilizations for millennia and can continue to do so if approached with wisdom, preparation, and respect for the powerful natural forces it represents.